Teresa’s passport to a new life with Down syndrome

March 29, 2014

Antonia Zerbisias

Posted with permission from Toronto Star

Teresa Heartchild is in the dining room, flashing her new Visa card.

She’s proud she can take her brother-in-law, Bill James, out for coffee and doughnuts after they power-walk through their Bedford Park neighbourhood.

On the other side of the table, her older sister, Franke James, props up her iPad, which is playing a video of Teresa applying for that card at the bank.

Asked to share her PIN, Teresa is shocked: “It’s personal. I’m not supposed to tell.”

At 49, Teresa is finally handling money. For the first time ever, she knows the price of orange juice. She can distinguish between bills and coins.

“She just never had any training,” Franke explains, adding that Teresa has, despite attending many day programs, been “cocooned” all her life.

Now that she’s living with Franke and Bill, Teresa has been getting lessons on independent living. Not that she will ever be on her own. She was born with Down syndrome and, despite her boast that she “can walk faster than a speeding bullet,” she faces mobility as well as other challenges.

But not nearly as many challenges as Teresa and Franke’s four other older siblings — all but one have asked not to be named in this story — believed she had when their elderly father Joseph could no longer care for her in the condo they shared. Teresa had lived with him since her mother died in 1999.

That’s why, on Nov. 27, and against her father’s wishes, those siblings had Teresa admitted to Toronto’s Rekai Centre, a long-term care facility filled mostly by people much older and less able than she is.

Franke and Bill believe Teresa was made out to be less capable than she is now proving to be. They charge that Teresa’s siblings worked to get her on a “crisis list” that would move her into “a nursing home.”

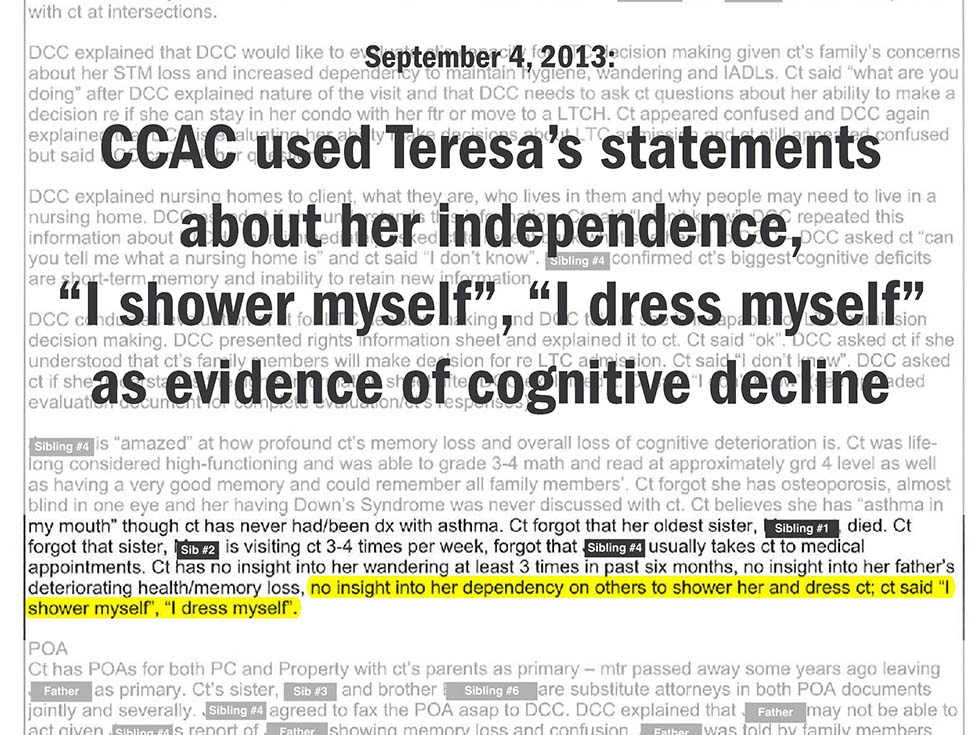

They claim the Community Care Access Centre (CCAC), which deemed her eligible for long-term care, “ignored” its own positive observations about Teresa’s behaviour. They say the system that moved her into the Rekai Centre so quickly was “manipulated” to manufacture a crisis that didn’t exist.

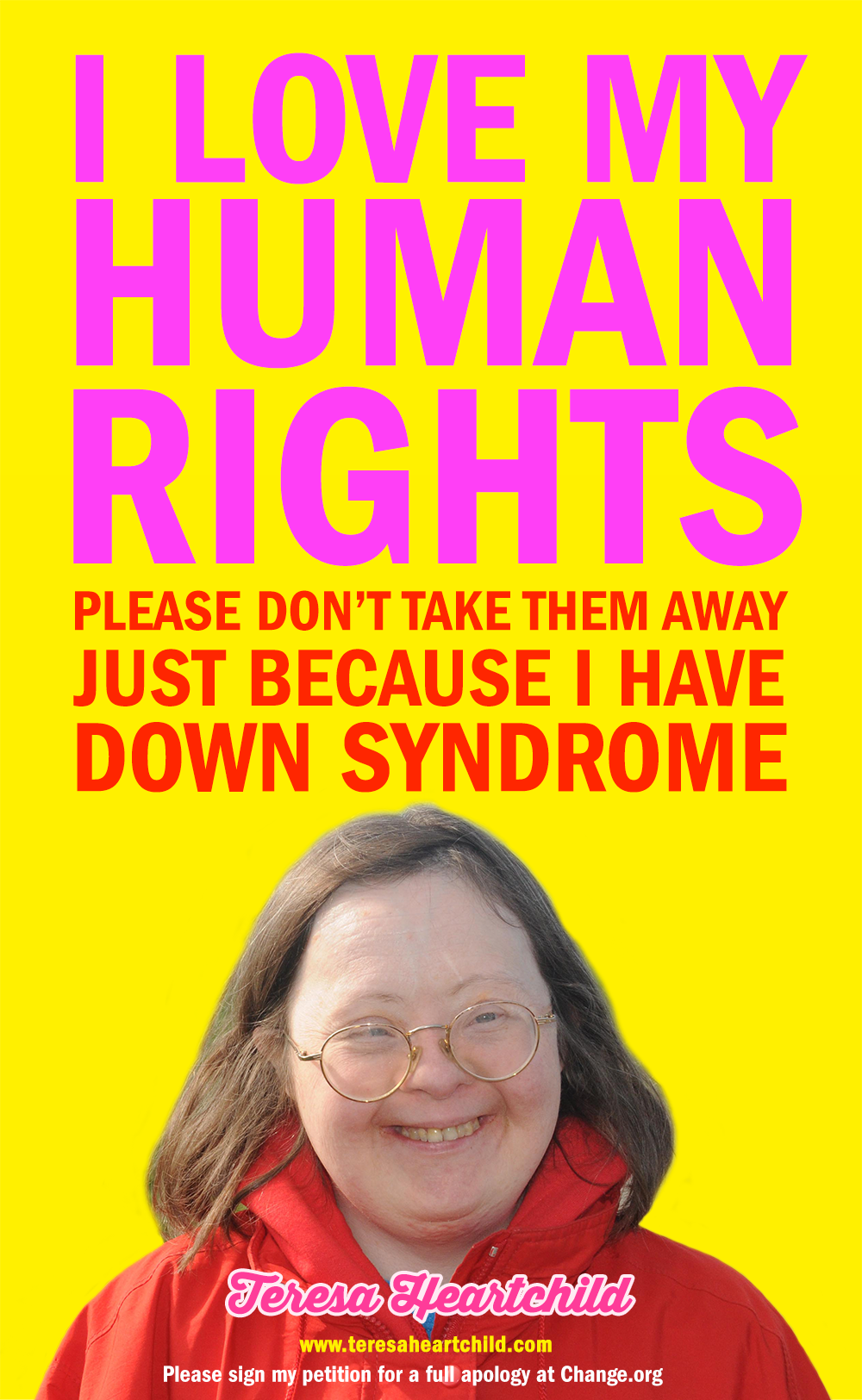

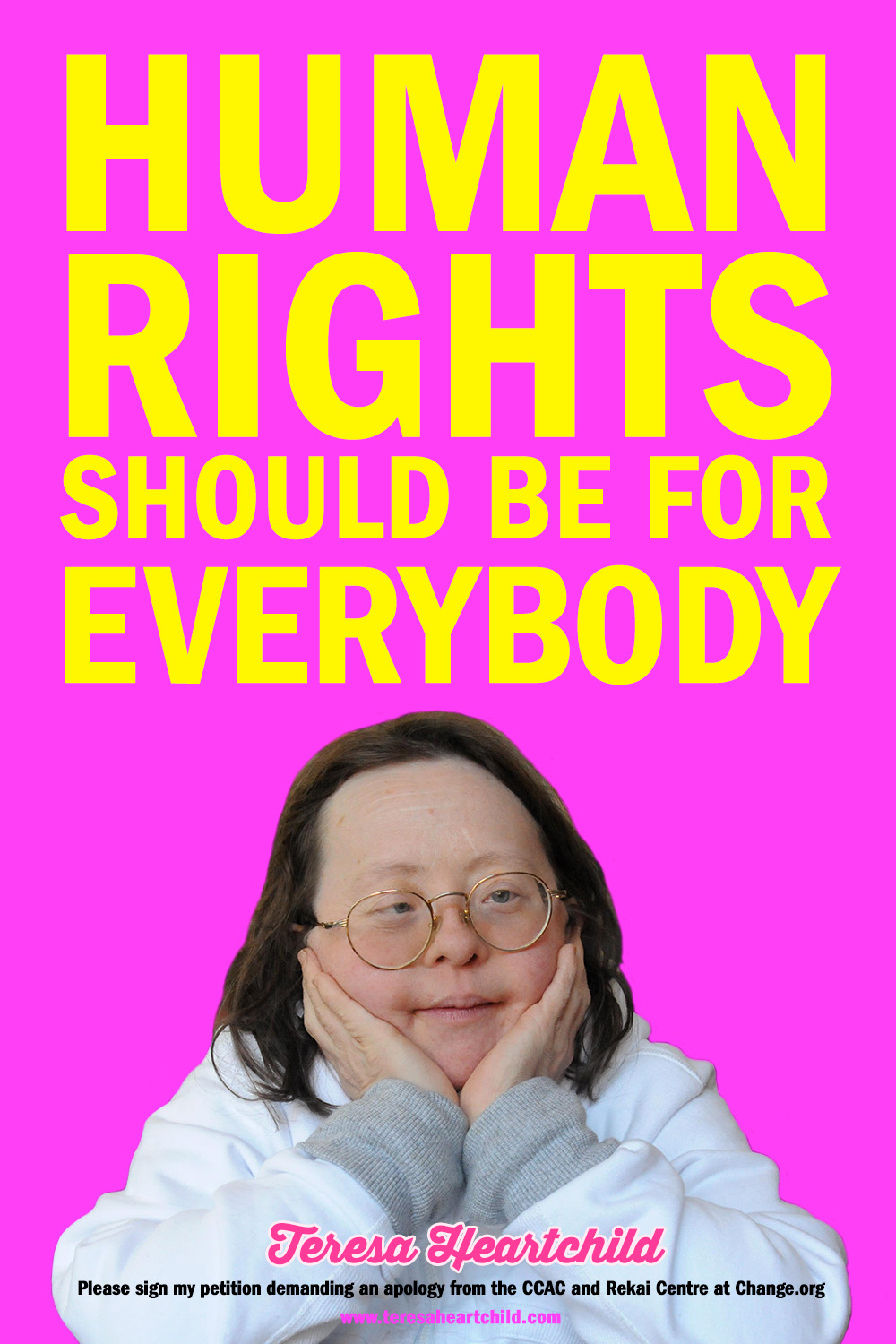

“The fact is, Teresa’s human rights were taken away,” insists Bill. “We want to share her story because we want people to know the truth about how the system works.”

Bill and Franke, both writers and artists who work at home, are angry — angry at the social service agencies that assessed Teresa as showing signs of dementia, angry that she was placed in “a nursing home,” angry at Teresa’s family.

Now they want apologies on Teresa’s behalf — and last week they got one. Toronto Central CCAC CEO Stacey Daub posted one on a petition Teresa and Franke put online.

“My siblings were desperate, but they didn’t have to be because we had offered to take care of Teresa for the rest of her life,” says Franke, producing a stack of emails between her and the rest of the family.

“If you had asked me a year ago to take her, I would have said, ‘No, let’s look at other options,’” she continues. “But once I got the sense that they were serious about putting Teresa in a nursing home, we stepped in.”

In January, Franke took Teresa’s case to the provincial Select Committee on Developmental Services, where she testified that the consent and capacity laws are “easily abused” and that “disabled and disadvantaged people are getting hurt.” She has even filed a complaint with the Human Rights Tribunal.

None of this is a knock on Teresa’s other siblings, who have doted on her all her life, taking her to their cottages, making sure she makes it to medical appointments, having her over for meals and holidays. In fact, every year, her two dozen nieces and nephews make a “Christmas calendar” for her, marking off the days they will each take her to a movie, or shopping, a hockey game or on some other outing.

But now the anger and resentment — on both sides — are palpable.

A misunderstanding? Miscommunication? “Manipulation?”

Depends on whom you talk to.

Three of Teresa’s siblings would communicate solely by email. Only her sister Joanne Mills spoke on the record with the Star. She maintains that the Rekai Centre was just a temporary stop for Teresa, until a suitable group home could be found.

“The real story here is that there should be more group homes,” she insists in a brief interview, adding that the family acted out of concern both for Teresa and their father. “Because no family member stepped forward to say that they would take her — we truly did not know that (Franke) and her husband would take Teresa — and no group homes were available, there was nowhere else for Teresa to go.”

It’s an all-too-common situation when parents of adult children with Down syndrome grow too old, or too ill, to care for them, despite government supports, community programs and social services. That’s because people with Down syndrome are living longer — so much longer that even their siblings are themselves ailing or otherwise unable to take them in.

“We have an aging population of Down syndrome clients,” notes Julia Oosterman, director of Communications and Stakeholder Relations at Toronto CCAC. “Appropriate housing — supported living, group homes etc. — is an area that we need to plan for as our population ages. Long-term care, while it may be the only available option, may not be suitable, and the health-care sector needs to consider how we plan for this.”

For her part, Mary Hoare, chief executive officer of the Rekai Centres, writes in an email: “It may not be ideal, but the top priority is always to ensure that, if someone is in urgent need and we have the space and capability to take them in, we will do so, and they will be safe and well cared for.”

But Bill and Franke say there was no urgency for Teresa.

“We offered four times to take Teresa, but the CCAC was never informed,” Franke said.

According to Dr. Terri Hewitt, vice president of community programs and adult services at Surrey Place Centre, the need for group homes is urgent. She counts 215 adults in Toronto on the waiting list. Of those, 102 are “ready” for placement now, while 59 are considered urgent and high-priority.

“If you’re in long-term care because you don’t have somewhere to live, then you become high priority,” Hewitt explains, avoiding the specifics of Teresa’s case. “If you’ve been transferred temporarily to long-term care placement to keep you safe, you would be escalated on our priority list. We would be actively looking for something. The more high priority you are, the more you are identified when vacancies come up.”

Hewitt can’t provide figures for how many adults with Down syndrome end up, at least temporarily, in nursing homes — but many do. Some for good.

“Even the most caring of families can have differences of opinion on how to proceed,” she admits. “It’s a difficult road to follow and preparation is the best thing that you can do.”

This particular story has a happy ending.

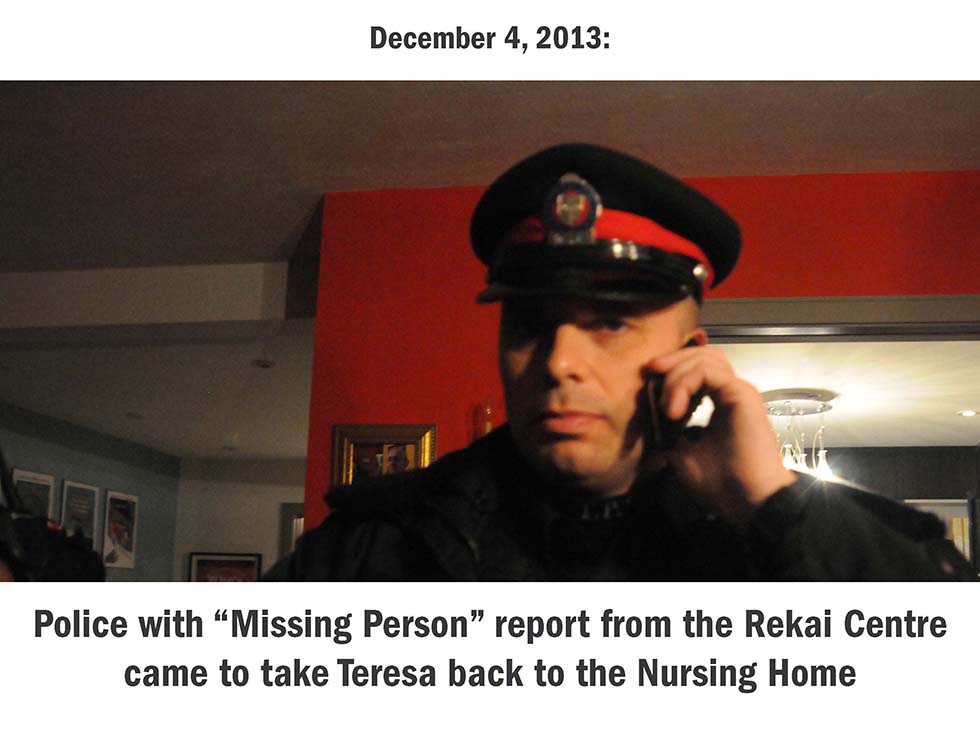

Unaware of the storm around her, Teresa is thriving in her airy new home. Since Dec. 1, when her father, Bill and Franke removed her from the Rekai Centre, she has been learning photography. She loves to play Scrabble. She cooks and she’s been hitting the road.

A new capacity assessment in January found Teresa to be “capable” enough for things like granting Franke and Bill her power of attorney for personal care. In February, she accompanied them to Washington, D.C., and all this month, she’s been on the West Coast, where she met David Suzuki.

“We’re really enjoying her,” says Franke. “It’s been an eye-opener.”

And for Teresa, it’s a wide new world.

![[iCopyright]](http://d2uzdrx7k4koxz.cloudfront.net/images/icopy-w.png) 2014 Torstar Syndication Services. All rights reserved. Licensed by Mrs Franke James on March 29, 2014. You may obtain additional permissions to reuse this article at the following iCopyright license record:

2014 Torstar Syndication Services. All rights reserved. Licensed by Mrs Franke James on March 29, 2014. You may obtain additional permissions to reuse this article at the following iCopyright license record: